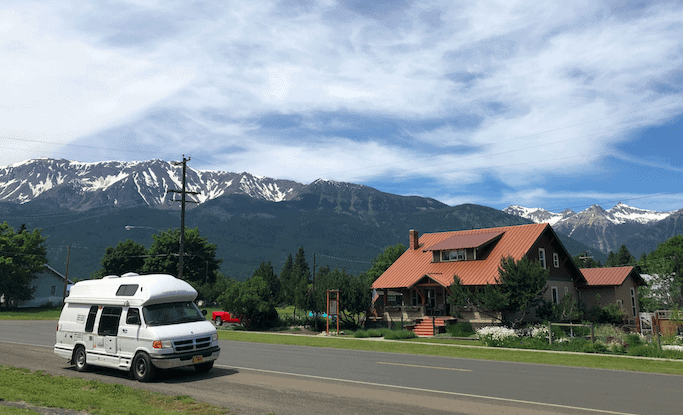

Leaving Wallowa Lake

When I left Wallowa Lake, I stopped at Iwetemlaykin Heritage Site. Iwetemlaykin means edge of the lake and it was part of the vast homeland for the Nez Perce (Nimiipuu) and the start of the Nez Perce Trail.

As I crested the hill and looked down over the grasslands of valley below, a wave of sadness overcame me. As if they were still there, in my mind I could see the Nez Perce Indians milling about in the lush open field at the tip of Wallowa Lake. Kids running and playing, horses and cattle grazing, women curing fish or mashing camas root. This was the summer home of the Nez Perce and the starting point of the Nez Perce Trail. Not a trail the tribe followed to hunt and fish on their magnificent appaloosa horses, but a trail of forced evacuation from an area that had been their home since time immemorial.

The area where I spent a month as a campground host was home to the Wallowa Band of the Nez Perce (Nimiipuu) until 1877 when the US government soldiers forced them to leave. Despite having a treaty that clearly delineated the land as theirs, despite the fact that they had lived here forever, despite that fact that the white man was the invader, the native people of Wallowa Valley were forced from their homeland. They began an 1170 mile forced march, where they were attacked 18 times and lost many of their people, most of their cattle and their way of life.

The tribe first were hoping to stay with their allies in the Crow Nation in Montana, but were turned away. They then tried to escape to Canada to seek asylum but ended up surrendering just 40 miles from the Canadian border, defeated from so many battles and a harsh flight across four states and rugged mountain passages. It is here that Joseph delivered his famous remarks :

I am tired of fighting. Our chiefs are killed; Looking Glass is dead, Too-hul-hul-sote is dead. The old men are all dead. It is the young men who say yes or no. He who led on the young men is dead. It is cold, and we have no blankets; the little children are freezing to death. My people, some of them, have run away to the hills, and have no blankets, no food. No one knows where they are—perhaps freezing to death. I want to have time to look for my children, to see how many I can find. Maybe I shall find them among the dead. Hear me, my chiefs! I am tired; my heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever.

Of course many of his people died anyway, when they were shipped in unheated railcars to Prisoner of War camps in Kansas for eight months and then sent to reservation in Oklahoma where many of them got sick and died. Eventually they were relocated to Colville reservation where Joseph continued to lobby for the rights of Native Americans and that America’s promise of freedom and equality would be extended to include all people. Alas, we know how this story turns out. Joseph never did return to his beloved Wallowa Valley, never returned to his father’s grave, never hunted or fished or paddled a canoe in the beautiful area where I spent a month this summer.

When he died, his doctor said the cause of death was a broken heart.

The town of Joseph is named after him. In some ways it feels cruel to me that this place hold his name, yet he was never able to return. And the people who we took this land from have not been able to come back to their motherland.

But of course, everywhere we live in this country is stolen Indian land. Portland and Boston and Washington, DC. The Wallowa mountains and the Adirondack mountains. The Columbia River and the Mississippi River. Everywhere I am visiting on my journey once was home to native people, most who have been forcibly removed from their homelands.

I think about this as drive away from Wallowa County, wondering what, if anything, I can do about the wrongs my country did to the native people. The only thing I can come up with is to do no more harm and to continue to educate myself about the native peoples of the lands I will be traveling through.